Measuring the Speed of Quantum Information

By Yariv Yanay, PhD

When discussing qubits and quantum computers, we usually think of them in terms of digital calculations (most notably Shor’s algorithm to factor prime numbers) and the advantage they have over classical algorithms. But while the field has been advancing at breakneck speed for the last decade and more, the fidelity of current devices remains far from what is required for such applications. This is because these requirements are very stringent: digital algorithms generally need to be able to run a full calculation without a single mistake. For an application like factoring a 2048-bit number, such as the ones used in modern encryption, this corresponds to an error rate of less than one in 108 after error correction algorithms are applied. But while digital calculations remain out of reach, there is a wide range of applications whose requirements for fidelity are much less. Generally, these are applications where small amounts of infidelity and decoherence lead to a result that is proportionally close to the desired one, rather than throwing off the calculation completely. One application that I have long been interested in, as a physicist, is the idea of quantum simulation. That is to say, using one quantum system as an analog for another, more complicated one. Why would we want to do that? Well, the systems we try to understand as physicists are often messy, with many more variables and degrees of freedom than we could ever hope to grapple with. Instead, we usually write down simple models, with few degrees of freedom, that we believe capture the essence of the real system. Quantum simulators allow us to realize these simple models in the lab, helping us better understand them, and in turn the real systems that inspired them.

Hard-Core Physics

Quantum simulation, as described above, is a very broad term – there are many physical systems and many models that one could be interested in. When we began our current collaboration a few years ago, we set out to find the intersection of what was interesting to explore, and what our collaborators at EQuS could realize in the lab. The result, described in our theory paper, was a kind of phase diagram depending on the parameters of the system – its coupling strength,  , compared to its frequency

, compared to its frequency![]() and anharmonicity

and anharmonicity ![]() . We were particularly interested in what systems we could explore with transmons, the current variant of superconducting qubits that is most robust to noise and decoherence.

. We were particularly interested in what systems we could explore with transmons, the current variant of superconducting qubits that is most robust to noise and decoherence.

Which many-body models can be realized by an array of qubits, depending on its parameters. Cyan shading highlights the area accessible with transmon qubits.

From this initial analysis, we decided to focus on the “Hard Core Boson” model: a system made up of particles (bosons) that strongly repel each other (have a “hard core”) to allow only one particle per site. There are many reasons why this model is interesting: it is a strongly-interacting many-body system, a class of models which physicists are very interested in, and it is hard to calculate – there is no analytical solution, and numerical calculations scale exponentially with the number of sites. The result, a year or so later, has now been published: in Probing quantum information propagation with out-of-time-ordered correlators we explore the Hard Core Boson model on a 3×3 lattice of transmons.

The experimental chip

Information Propagation

When we first calibrated our operational 9-qubit chip, having overcome many experimental challenges, we were faced with a dilemma: what should we measure?

There are many measures of many-body behavior, from correlation functions to subsystem entanglement entropy. For our first experiment, we set our sights on something a bit more exciting: the propagation of quantum information. In other words, once we perturb one side of the system, how long does it take until the other side notices?

In an empty system, when we start with all qubits in the ground state, this is an easy measurement. We simply add an excitation and let the system evolve. Information, in this case, is carried by the excitation itself, and we can check for its arrival by measuring the excitation of the qubits across the system.

But what happens if the system is not empty? If we start at some excited state and add an additional excitation. There is no way to track “our” excitation, as opposed to the other ones – quantum particles are interchangeable.

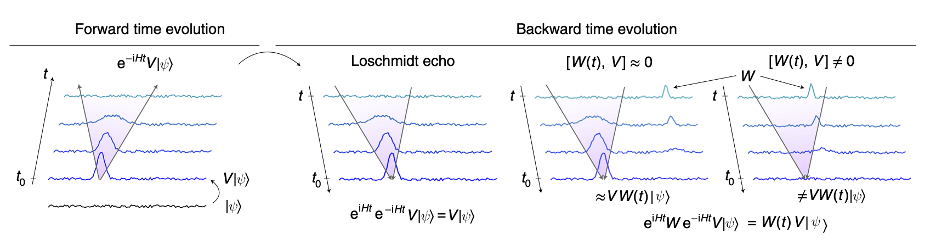

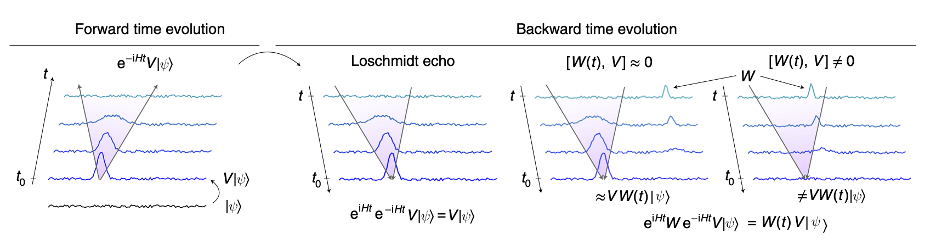

Enter the OTOC, or out-of-time-ordered correlator, a mathematical object favored by theorists to examine information propagation. There are multiple ways to describe it, but perhaps the most intuitive is in terms of the butterfly effect.

Quantum Butterflies

To understand OTOCs, first imagine a simpler process. We set our system to some initial state ![]() and then perturb it with a local operator

and then perturb it with a local operator ![]() (for example, adding an excitation). As we let the system evolve, this initial excitation is scrambled by the dynamics, and after a while it is no longer clearly localized. However, the information is still there: if we now reverse time and run the evolution backwards, we would be able to recreate the perturbed state. This is called a Loschmidt echo.

(for example, adding an excitation). As we let the system evolve, this initial excitation is scrambled by the dynamics, and after a while it is no longer clearly localized. However, the information is still there: if we now reverse time and run the evolution backwards, we would be able to recreate the perturbed state. This is called a Loschmidt echo.

Using forward and backward time evolution to probe the information light cone.

To study the propagation of information, we add an intermediary step. As before, we start with ![]() , apply the perturbation

, apply the perturbation ![]() , and let the system evolve forward in time. But now, we add a second local perturbation,

, and let the system evolve forward in time. But now, we add a second local perturbation, ![]() , at some distance from

, at some distance from ![]() . We then rewind time, as before. What do we expect to see?

. We then rewind time, as before. What do we expect to see?

The result depends on the very concept of information propagation. If we imagine a kind of “information light cone”, emerging from ![]() and expanding with time, then after the forward time evolution, all of the information about the perturbation lies within some distance from that origin. If

and expanding with time, then after the forward time evolution, all of the information about the perturbation lies within some distance from that origin. If ![]() sits outside this cone, then it does not disturb this information, and as we rewind time,

sits outside this cone, then it does not disturb this information, and as we rewind time, ![]() is recreated. However, if

is recreated. However, if

![]() is within the cone, it can exert a butterfly-like chaotic effect and so rewinding time will not recreate the original

is within the cone, it can exert a butterfly-like chaotic effect and so rewinding time will not recreate the original ![]() perturbation.

perturbation.

In the experiment, we cannot reverse time, but we found that we can do something equivalent: reverse the system dynamics. By applying a specific set of pulses, we reverse the Hamiltonian, allowing its forward time evolution to perform the reversal of the regular dynamics.

Seeing the Light Cone

In the lab, we began by performing the experiment outlined above on a resonant (or degenerate) lattice, one where all qubits have the same frequency, and so excitations can hop around freely. The results, shown below, are quite remarkable, both in their agreement with numerical simulation and in how clearly we can observe the information light cone.

The information light cone in a degenerate lattice, as experimentally measured by extracting OTOC. Here qubits are grouped by their distance from the initial excitation.

In the figure above, we have on the left the simple experiment we outlined originally for the system in its ground state: a single excitation is added, and its location is tracked. The four columns on the right represent OTOC experiments. We see that in the absence of other excitations, the pictures are the same (note their time axis is different) – as noted above, a single excitation is itself the information.

The OTOC formalism, however, allows us to go beyond the ground state. In the next three columns, we start the system with one, two, or three excitations, and repeat the OTOC experiment. We are able, again, to extract a clear light-cone of information, as qubits farther away are unaffected by the perturbation until later times.

You might note, though, that while we have obtained these light cones, they seem unchanged by the presence of excitations. Adding more particles to the system does not inhibit or aid the flow of information. To see the effects of many-body physics, we need to go to the disordered case.

Law and Disorder

The information light cone in a disordered lattice, as experimentally measured by extracting OTOC.

In our final experiment, we added one extra ingredient. Instead of tuning all qubits to the same frequency, we added a random offset, roughly of the same scale as the strength of the coupling between them. Now, excitations have a harder time moving around the lattice, as they must overcome these energy differences. In fact, in the figure above, we see that the disorder can localize excitations and the information they carry: in the absence of other excitations, the information from one corner never reaches all the way to the other side of the lattice.

In the single-particle case, this effect is called Anderson localization, and for non-interacting particles, it is expected to occur regardless of the initial state. But here, in the strongly-interacting case, we see something quite different: as we add excitations, the light cone expands, outwards and downwards. The extra particles allow information to move farther out, and move faster.

Finally, we put all this together in figure (b) above. Averaging over twelve different random disorder realizations, we plot the light cone for each case, and we see clearly how it is affected by the presence of extra excitations, going from the slow, sometimes-localized gray curve to the faster red curve. We observe the red curve, in this log-linear plot, implies a logarithmic spread of information, which is expected in some many-body-localized systems.

Next: More Qubits, More Data

The work on this experiment concluded early last year, with our paper making it through the editorial process in the fall. In the meantime, things are moving quickly on the next chapter: a larger chip, longer lived qubits, and better controls, promising new and exciting results in this area.